Imagining a Positive Berlin 2050 — A Conversation with Journalist Ida Ovesson

Ida, how did you come to write a future scenario about Berlin—and what shaped your path into journalism?

Ida: I grew up in the forests of northern Sweden, surrounded by nature. That environment shaped me, and environmental questions have always felt personal. Later, living in Denmark and Germany opened up completely new perspectives. Coming from northern Sweden, climate action felt much more visible in Germany — partly because of the larger population, but also because there were so many demonstrations and so many people who were vegetarian or vegan. Climate engagement seemed more present at an individual level, even though Sweden of course also has highly committed climate activists, like Greta Thunberg.

This experience didn’t necessarily change how I think about climate journalism, but it did influence how I view climate action. As a journalist, I don’t participate in demonstrations myself; my way of contributing is through reporting on these issues. That’s where climate journalism fits into my life.

My path into journalism happened gradually. In eighth grade I interned at a local newspaper, discovered my interest in photography, and realised I loved writing long texts. When I joined an exchange program in Bavaria, I practised German and got fascinated by international storytelling. Over time I simply combined everything I cared about—writing, imagery, global perspectives. Journalism became the natural answer.

The Berlin 2050 scenario was entirely my own idea. During my internship at Deutsche Welle, I had to do a project for my master’s program. I had just taken a course in future journalism, and something clicked. I realised: you can report about futures just as you report about the present. That felt boundary-breaking. I suggested creating a future scenario—initially comparing several cities—but since I lived in Berlin, it made sense to start right where I was.

How did you construct your Berlin 2050 scenario? What was difficult about making assumptions about the future?

Ida: The scenario is grounded in real expertise and in the knowledge available at the moment. I interviewed twelve specialists across mobility, food, energy, fashion, and water — plus one “future archaeologist,” making thirteen interviews in total. I also contacted several additional experts who either did not reply or shared background information without participating in a full interview.

My guiding question for all of them was simple: If Berlin reached climate neutrality by 2050, what would your field look like? What would have changed? What steps would have been necessary? To complement the interviews, I read IPCC reports, local transportation studies, building concepts, and articles on urban development. You quickly realise that much of the future can already be seen in small early developments.

The hardest part was technology. It evolves so fast that concrete predictions feel risky. In my first draft, I wrote that Emilia used her phone to text her girlfriend Sophia — but an editor asked, “What if phones don’t exist anymore?” It was a good point. Maybe by 2050 we’ll be using lenses or something entirely different. So I removed many tech details to keep the scenario plausible rather than speculative.

Why Emilia Lives an Ordinary Day

I chose to write a “day in the life” because it makes the future accessible. If I had only listed trends in energy, transportation or food systems, it would have become another analytical article. But following one person—her routines, her commute, her small habits—allows the reader to imagine themselves in that future. It’s chronological, relatable, and grounded in daily life.

I didn’t have the space to include as many details as I would have liked, partly because the Deutsche Welle format is very strict. That structure had its pros and cons: I couldn’t integrate all the information I had gathered, but perhaps including everything would have overwhelmed the reader as well.

A Vision of Society Shift: From Fast Fashion to Repair Culture

One thing I learned is that societal futures depend on behavioural shifts. Fast fashion disappearing, repair culture growing, second-hand ecosystems expanding—these aren’t just lifestyle details. They change professions, patterns of consumption, and how people relate to resources. Several experts told me the same: jobs won’t vanish, they will shift. Someone will need to repair clothes, manage circular stores, or maintain sharing systems. It’s a reorientation, not a collapse.

What gives you hope for 2050—and what role should journalism play in shaping that future?

Ida:If I’m honest, Emilia—the protagonist—lives a version of my ideal life. Not literally, but in spirit. A world where climate transition is a collective effort, where people collaborate, help each other, and innovation is supported by society. Many experts told me the same thing: collaboration is the key, and it starts small. One expert phrased it beautifully: “We have to take it street by street.”

Constructive Journalism and the Future of Media

I believe in constructive journalism. It doesn’t ignore problems—but it highlights solutions and possibilities. Research suggests that one reason people avoid the news is that it often feels overwhelmingly negative and fast, although there are of course other factors involved. We have “fast fashion” and now we have “fast media.” I think journalism must shift: not necessarily toward long texts, but meaningful stories, short or long, that still carry emotional depth.

Maybe the future is more feature-driven, boundary-breaking, cross-format storytelling. And I don’t think AI can replace journalists completely. It can help us—but the human touch, the ability to listen, connect, feel—that stays essential.

What Gives Ida Hope for 2050

What gives me hope is imagining a world in which people collaborate more naturally, where environmental responsibility is shared, where innovation is guided by values, and where changes happen step by step—neighbourhood by neighbourhood, street by street. And that we can still create this world if we decide to.

We would like to thank Ida for her time and for this inspiring interview.

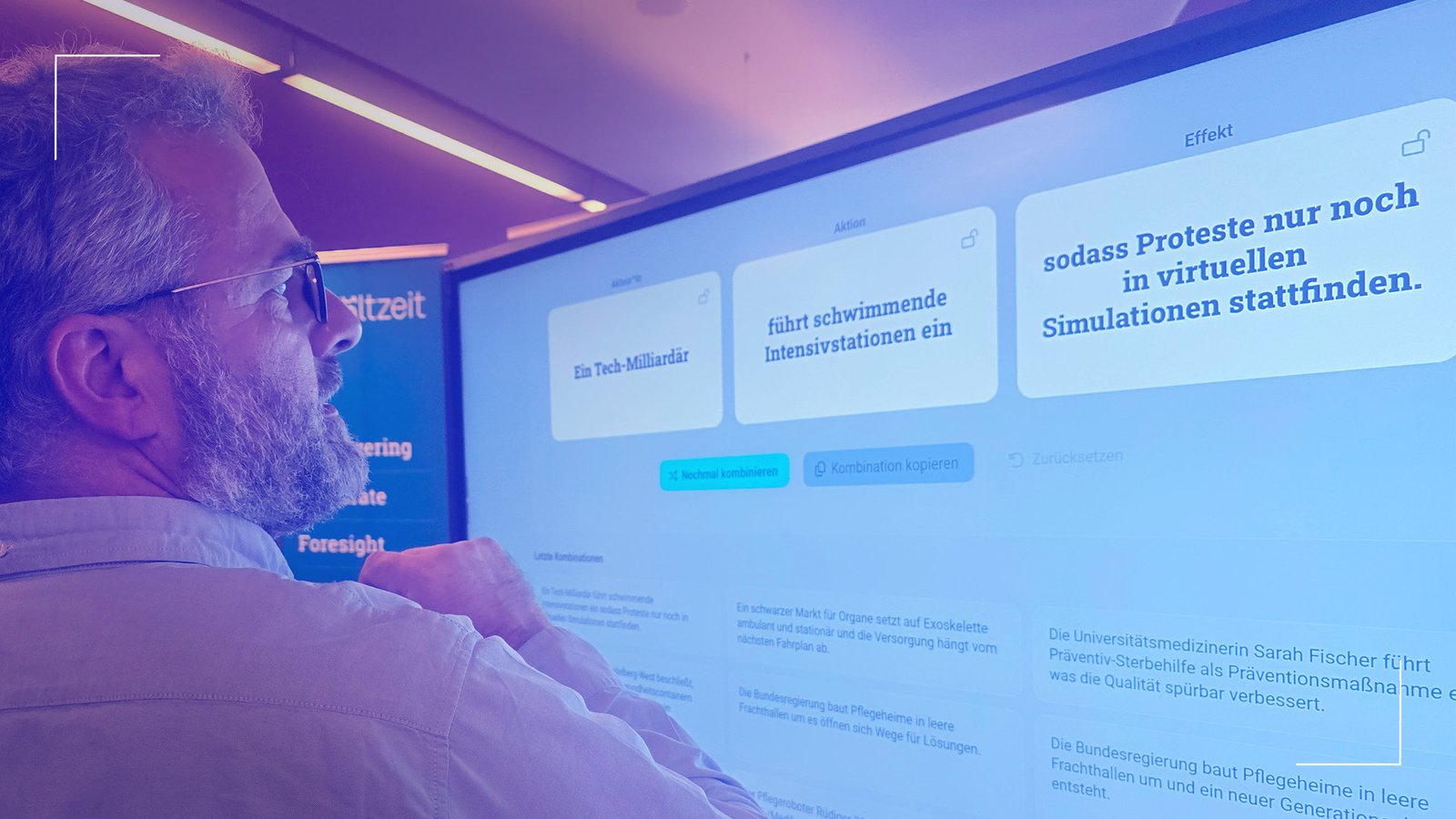

Why We at Schaltzeit Appreciate Ida’s Work

- It is deeply researched, grounded in expert insights.

- It translates complex systems into everyday life, making futures tangible.

- It embodies the idea that progress means resilience, not just growth.

- It invites readers to imagine themselves as active contributors, not passive recipients.

- It replaces the “hero narrative” with a heroic collective—activism, policy, innovation working together.

Links & Further Reading

Learn more about constructive journalism:

- Constructive Institute: https://constructiveinstitute.org/

The institute has played a major role in popularising and institutionalising the concept.

Research on news avoidance and how constructive journalism can counteract it:

- https://www-tandfonline-com.ez.statsbiblioteket.dk/doi/full/10.1080/1461670X.2019.1686410#d1e334

- https://journals-sagepub-com.ez.statsbiblioteket.dk/doi/10.1177/14648849221090744

- https://www-tandfonline-com.ez.statsbiblioteket.dk/doi/full/10.1080/1461670X.2024.2393131#d1e504

Recommended reading:

- Durstiges Land: Wie wir leben, wenn das Wasser knapp wird — Susanne Götze & Annika Joeres

Ida notes that several readers felt her scenario resonated with the themes explored in this book.

Future-focused productions that inspired Ida during her writing process:

- https://www.nrk.no/dokumentar/xl/slik-kan-global-oppvarming-pavirke-ylva-_4_-1.12535517

- https://www.aftenposten.no/norge/i/y4Ayzx/hva-skjer-med-syvers-somre-norge-blir-det-nye-syden

- https://www.dw.com/en/imagine-the-world-you-want-to-live-in-mumbai/video-71244674

A recent study on future journalism:

More of Ida’s journalistic work:

- https://europeancorrespondent.com/de/r/a-genderequal-city

- https://europeancorrespondent.com/en/r/is-europe-still-in-charge-of-its-batteries

- https://cphpost.dk/2025-04-28/art-culture/culture/tuno-an-island-running-out-of-time/

- https://europeancorrespondent.com/en/r/the-scandinavian-code-of-conduct

- https://europeancorrespondent.com/en/r/the-swedish-secret-to-a-genderequal-parliamen